Happy weekend Daybreak friends!

Matteo here for the fifth episode of the

Design Diaries. In the previous episodes we explored the

design goals,

antagonists,

resources, as well as the

players and powers that make up the game. Today we'll dive into how we designed the winning and losing conditions.

Daybreak has one way to win and three ways to lose

In order to win, players need to cut their emissions until they have reversed global warming.

At the same time, players have to protect their communities from a crescendo of crises, so that they can win before it gets too hot, it's too late, or too many communities are in danger.

Endangering too many communities is the core loss condition (more on this below). The other two – too hot or too late – are ancillary, but worth exploring first because they are tied to the question of when and how the game ends.

When is the game over?

Often one resource in a game acts at the clock. It gradually depletes and when it runs out, the game ends.

In cooperative games like

Pandemic and

Onirim, the clock is the player deck. In Daybreak, we have a large deck of opportunity cards, from which players draw each round to build their solutions engines. Since we encourage players to mine the deck in search of good cards (aka R&D actions), it wouldn’t make sense to make the game end when players run out of cards. It would also send a strange message, as if opportunities for climate action emerged at random and then expired if they were not immediately seized.

What about running out of time?

For several months we resisted setting hard stops in the game. It felt wrong to tell players they have X rounds to solve climate change, because the world won’t end in 2050 (the current horizon of many governments’ plans).

However, we observed that the length of the round tracker would set strong expectations, and often false ones. Some players would say “we have 10 rounds to fix this” at the beginning of games that would end after 3-4 rounds. While some felt relaxed about their time allowance, others were concerned about how long the whole game might take (“if the first round took us 30 minutes, we’ll be still here past midnight!”).

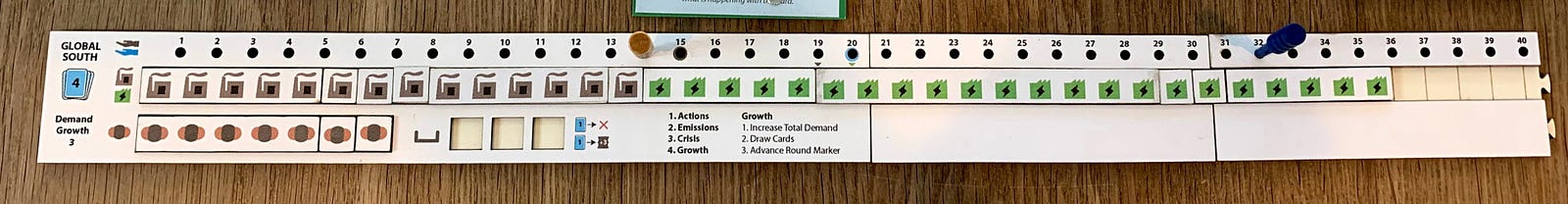

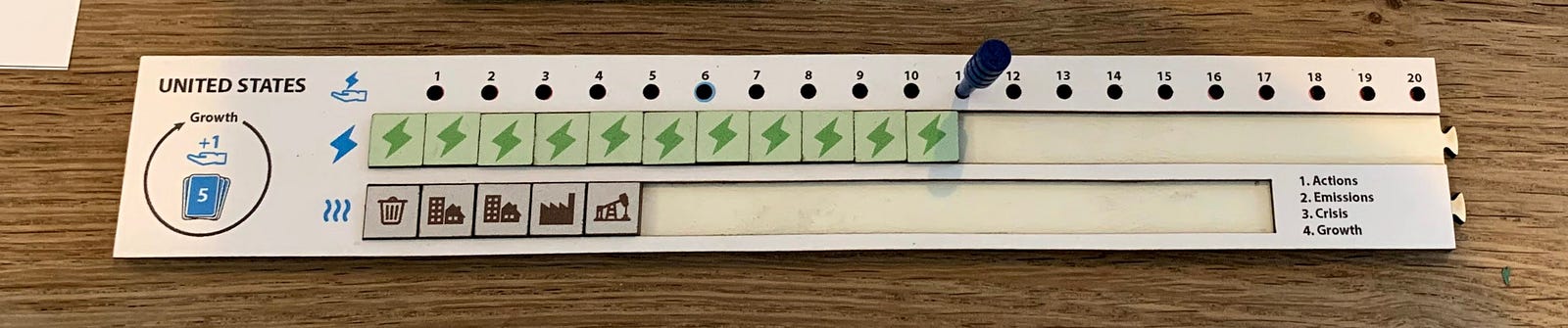

So to guide players' expectations and instil a sense of urgency, we progressively shortened the round tracker (from 12+ to 6 rounds) and defined a hard-stop point: if players haven’t won by the end of the sixth round, then it’s game over and you all lose. In all likelihood though, if players haven’t won by round 6, they have already endangered too many communities and triggered the core loss condition.

What about running out of carbon?

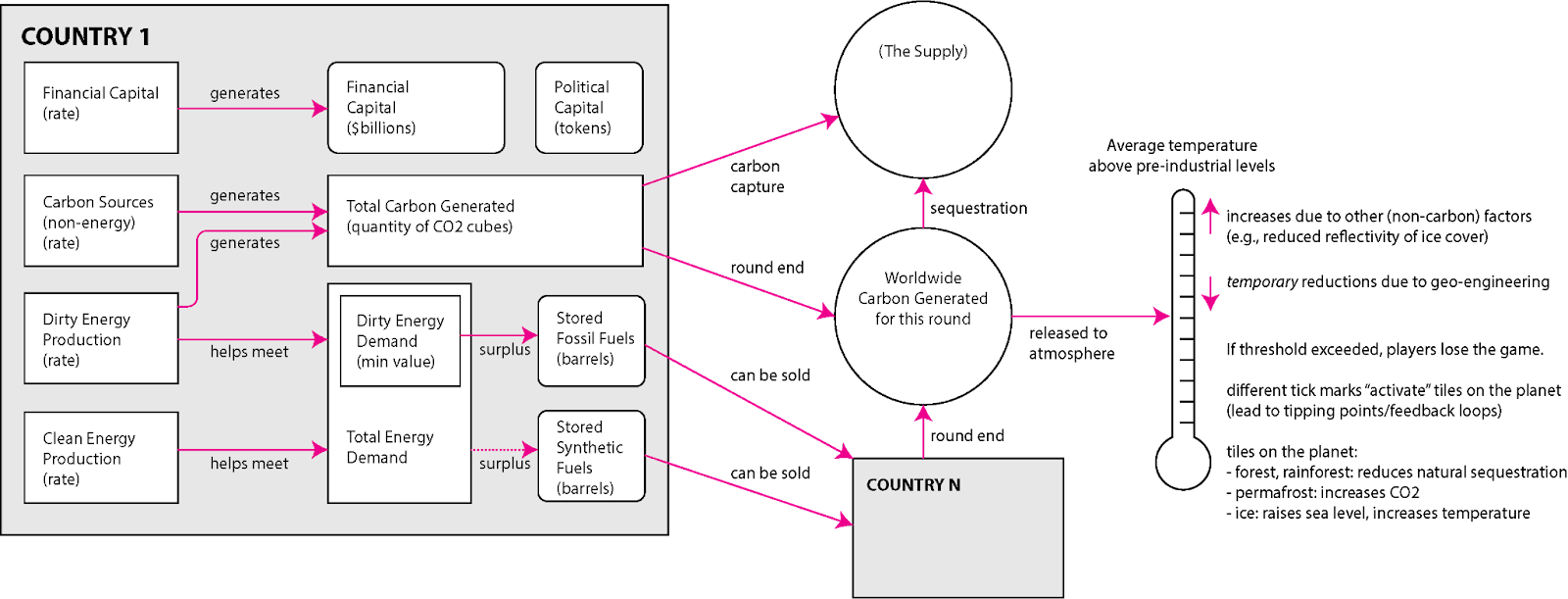

You can think of the thermometer in Daybreak as your carbon budget. Since (carbon) emissions are directly linked to global warming, in our early prototypes we set a cap to the total amount of carbon players can emit before the game is over and lost.

But just like with time, we know the world won’t end if global warming reaches 2.0ºC, although we also know that at those levels the conditions for humans (and many other species) to thrive will be severely impacted, and many places on our planet rendered

uninhabitable.

So while setting a loss condition at 2.0ºC might feel arbitrary, or “disturbing” as

Oliver Morton once told us, it helps us communicate that the higher the temperature, the more future generations will suffer. And like with the other ancillary loss condition, we tuned the game so that it’s rarely triggered. Normally players win or lose way before that point.

What is the core loss condition then?

When we started playtesting our initial prototypes with family and friends, the (only) loss condition was set at 2.0ºC.

At the time we also reached out to the

Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre to seek their advice on how the game was shaping up. On our first meeting,

Pablo Suarez made the unforgettable comment that climate action is “not merely a war on carbon”, which was a good summary of our game at that point. We realised that while the game was modelling the emissions cycle and energy transition, it didn’t include the human suffering and loss caused by climate shocks. And we didn’t have a way to represent the efforts to protect people and places from the impacts of those shocks.

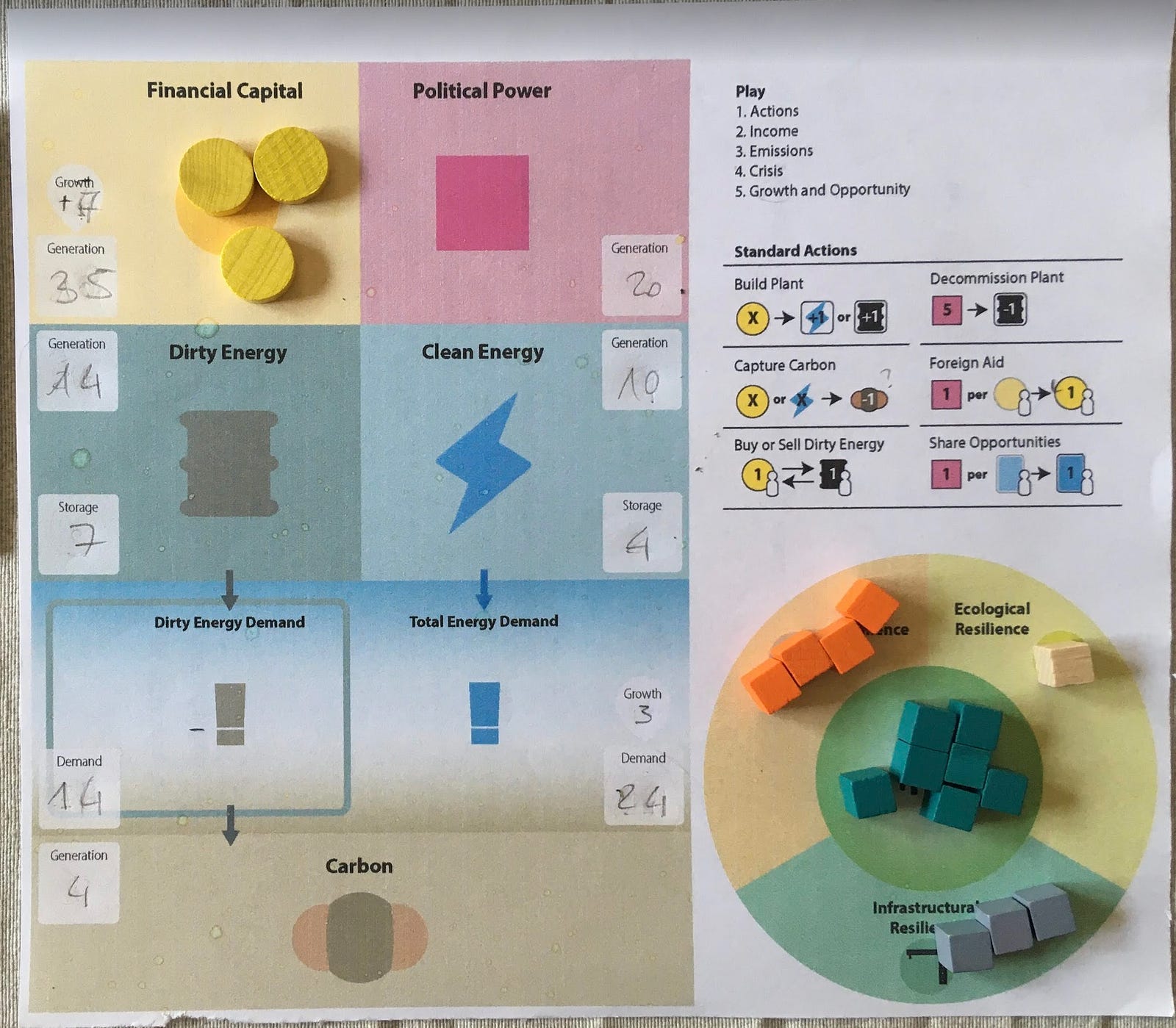

We had to include these dimensions in the game, so we gave each player a set of people tokens and introduced a new loss condition: you lose the game if players collectively lose N people. This centred protecting lives as a core climate goal.

We didn’t want to map people tokens to real population numbers. Doing that would have forced us to give each player a ton of tokens, especially to the player representing the Majority World. We also didn’t want the game to suggest that their entire population could be wiped by climate shocks.

Instead of trying to model populations, we wanted to focus on a threshold of suffering and loss, beyond which the consequences are unbearable or unacceptable.

Setting that threshold as a

collective number would indicate that people are equal, no matter which part of the world they are in. If people in the Majority World are suffering, it doesn’t matter how safe people in Europe or in the US are, because the game will be lost by everyone when that collective threshold is reached.

This is how it worked. Each player would place an equal number (10) of people tokens in the middle of the resilience “doughnut” on their player board. Then, when a crisis would cause some people to become “lost”, the tokens would be transferred in a coffin-shaped area on the game board.

It was a rather macabre metaphor, and it turns out also a misleading one. As our

Climate Centre advisors pointed out, people don’t have to be dead in order to be in trouble. It’s much more common for people to be displaced as a result of worsening climate and living conditions, than to be killed. To reflect this reality, we changed that state from being

lost to being

in crisis. This opened up the possibility of people

recovering, either being rescued by humanitarian interventions or improving their conditions thanks to socio-economic policies.

Still, when “people” became “people in crisis” they were moved from the centre of each player’s attention to the game board. That distance was both physical and psychological: once over there, it was harder to track how many tokens were in the crisis zone, and it felt like they belonged to nobody.

We realised we wanted players to feel attached to their people, both when they are safe and when they are in crisis. So we changed the loss condition: everyone loses the game if any one player has N people in crisis.

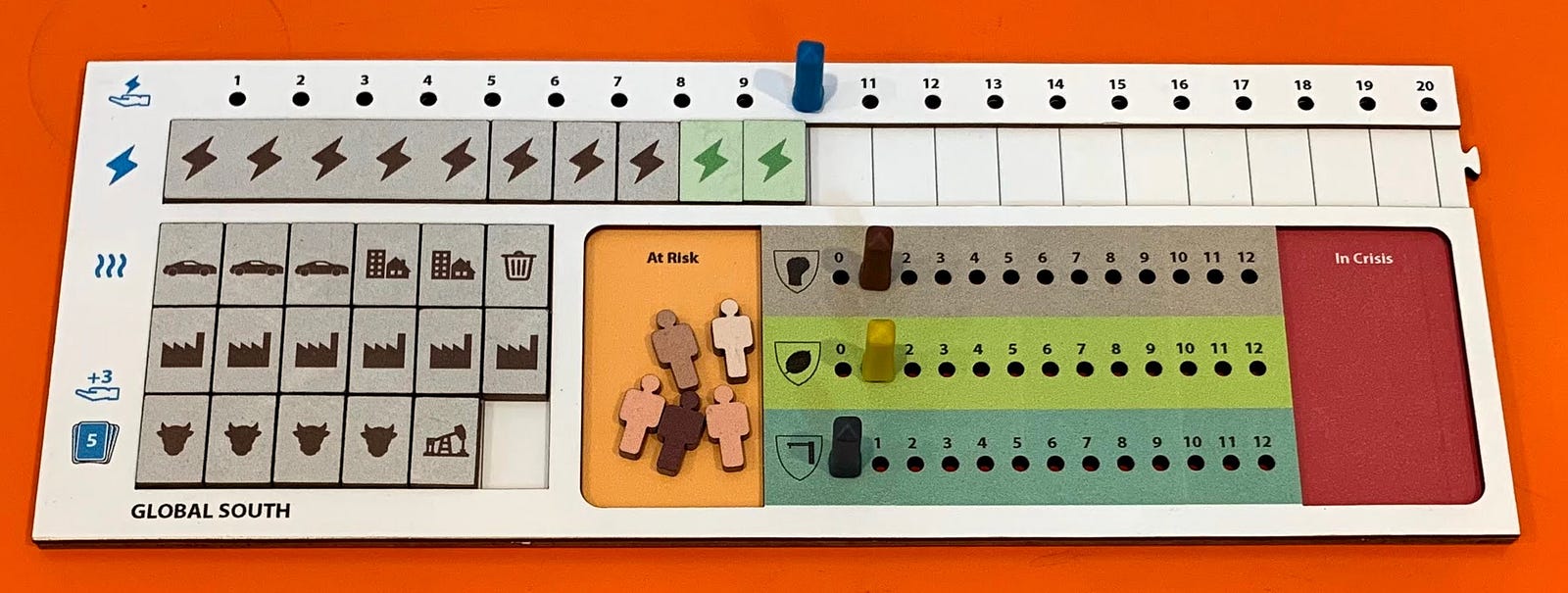

This shift meant changing the boards too. People in crisis would now fall through the cracks of the resilience doughnut, sitting unprotected outside of it. We noticed players would care much more about their people with these rules and layout, but it was still hard to grok how many tokens were in the crisis zone, i.e. how close each player was to triggering a loss for everyone.

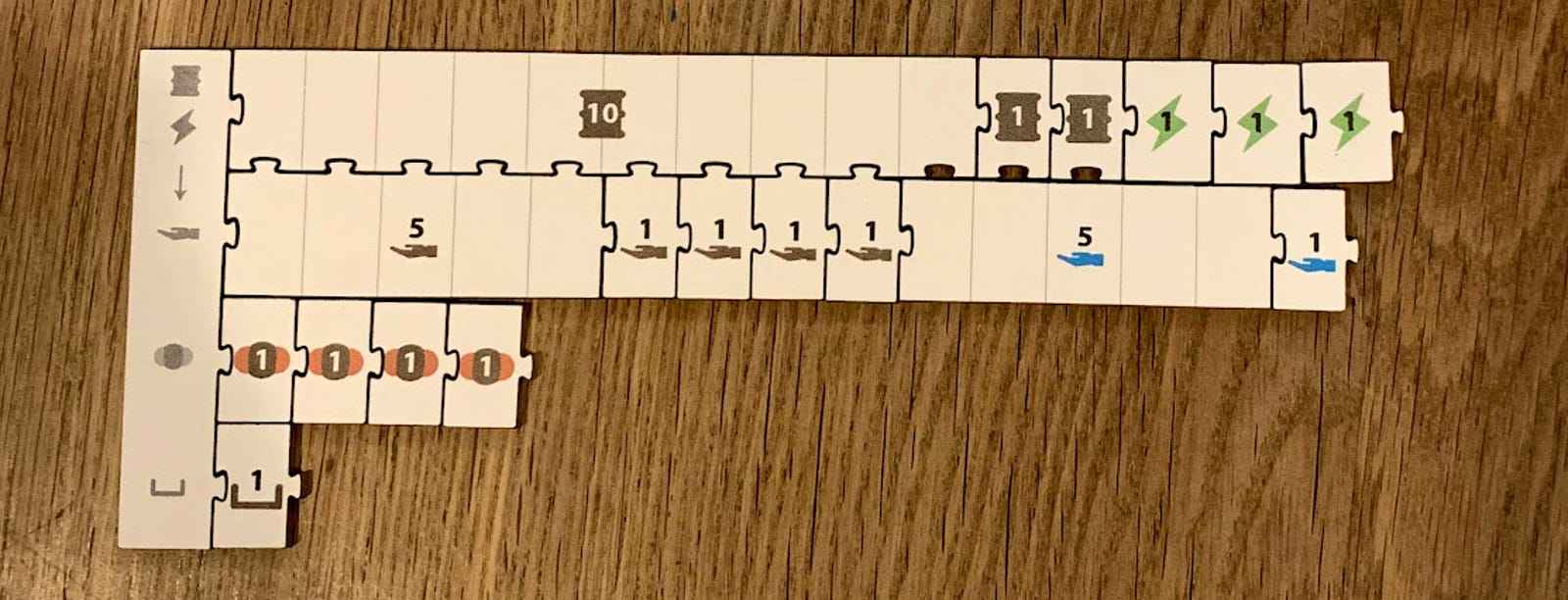

We then experimented with a more conventional track, in which each token in the crisis zone would occupy a designated space, and the danger level is very easy to read.

At that point we changed language and icons from “people” to “communities”, to highlight the societal scale of climate change impacts. Also, one too many playtesters confused the people icon for a gendered toilet sign 🚻

We wondered how granular we could go in representing the human suffering dimension of climate change. One experiment was a sliding scale, where communities could move from safety, to risk, to crisis and (hopefully) back.

Another experiment was to peg the number of communities in crisis to the number of cards people would draw each round.

Every additional community in crisis can have a meaningful impact on players, and make it harder and harder for them to win.

What is the win condition then?

The victory condition defines what players should strive for, and therefore what really, ultimately matters in a game. So when it comes to climate change, what does it mean to win? What is the ultimate goal of climate policy?

Our planetary climate system is breaking down because for centuries, certain human activities have been generating more greenhouse gas emissions than our planet can absorb.

To prevent catastrophic levels of global warming, cutting those emissions at source is imperative.

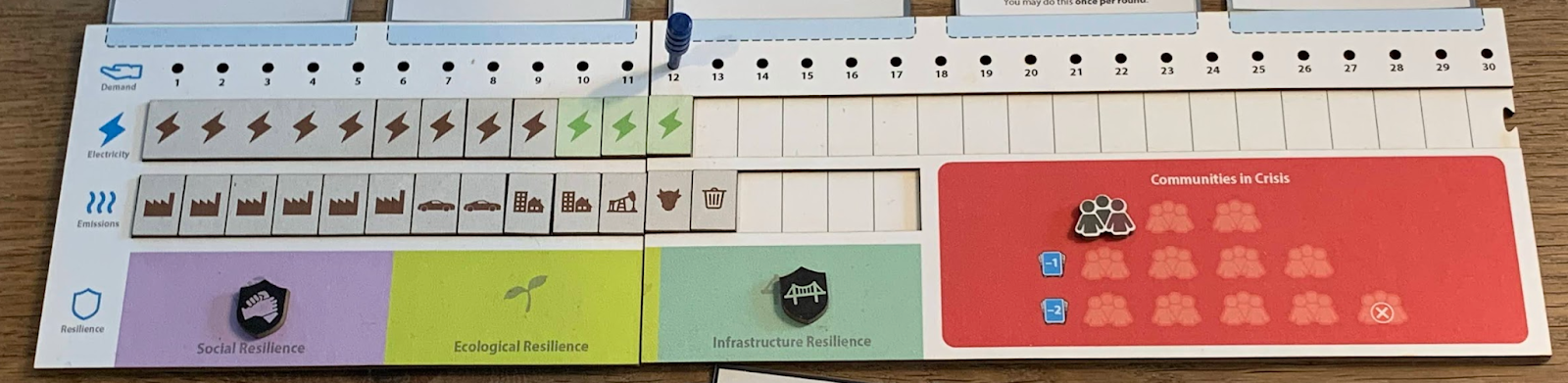

In Daybreak, each round all emissions from all players are dumped on the game board. Some of those get absorbed by carbon sinks on the world map. Then the remaining

net emissions drive up global warming on the thermometer. This causes a cascade of crises, from extreme weather events to global crop failures and political shocks, which if left unchecked will overwhelm players (to learn more on how we modelled this feedback loop, see

Design Diary 2 - Antagonists and Impacts).

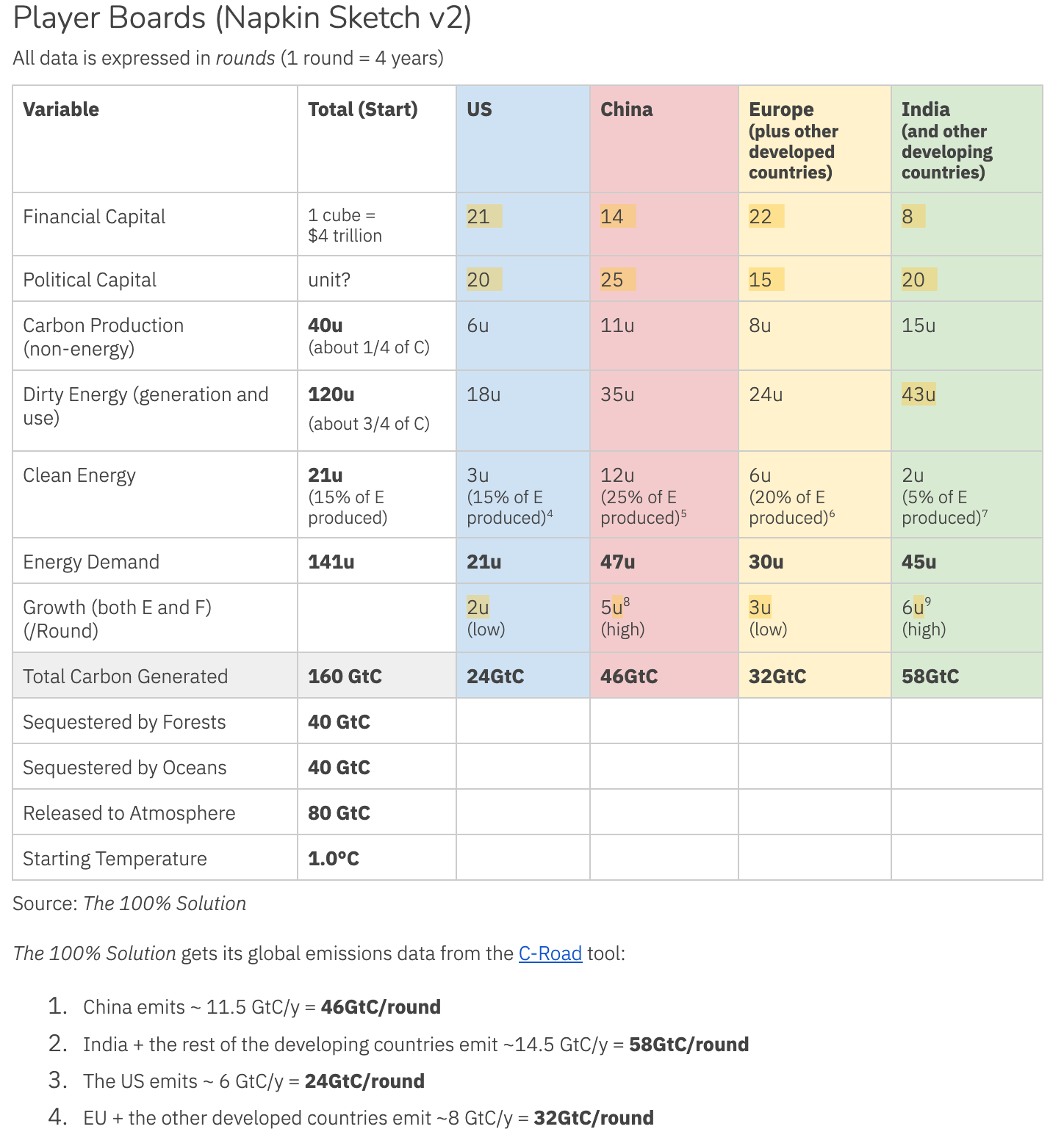

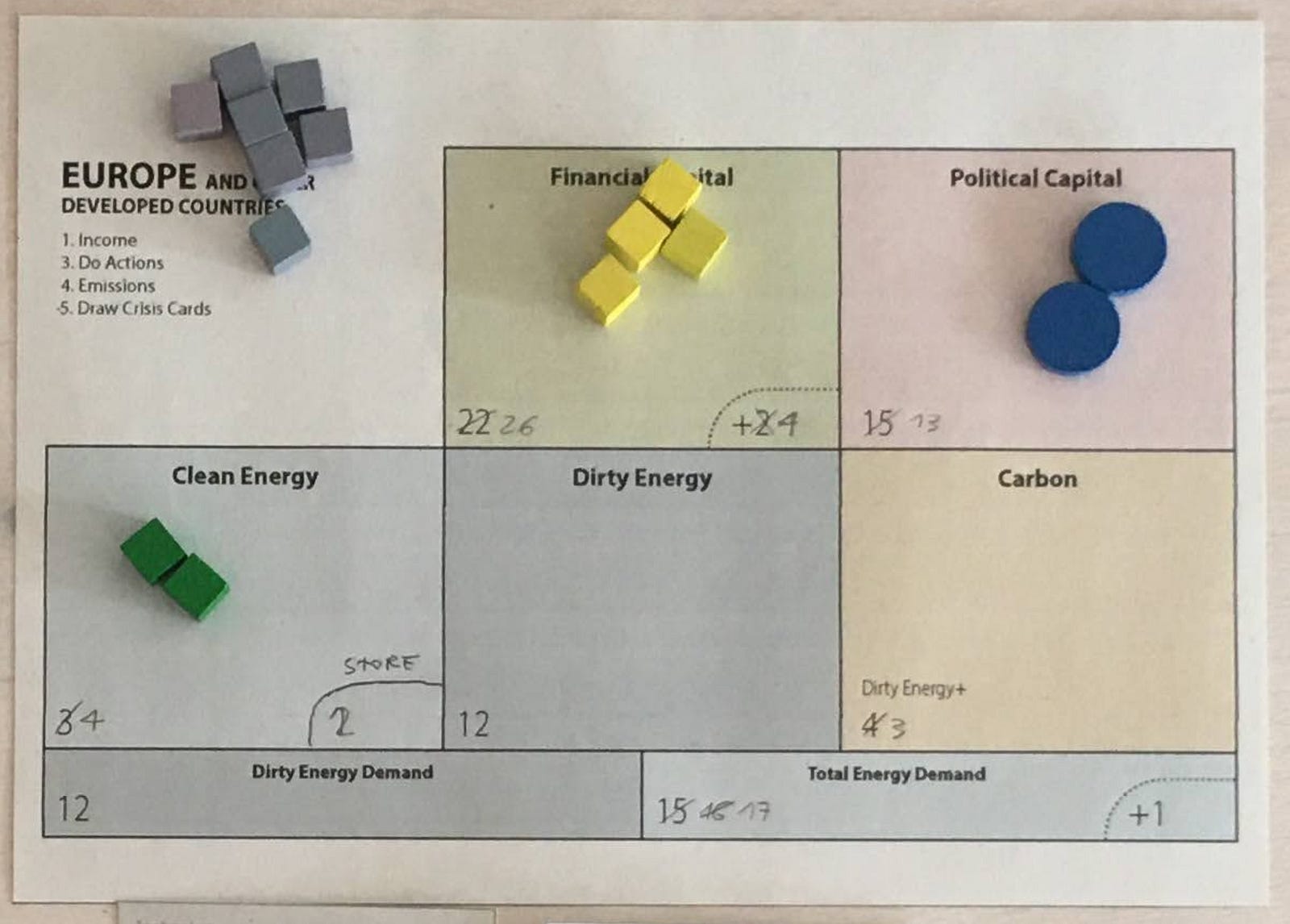

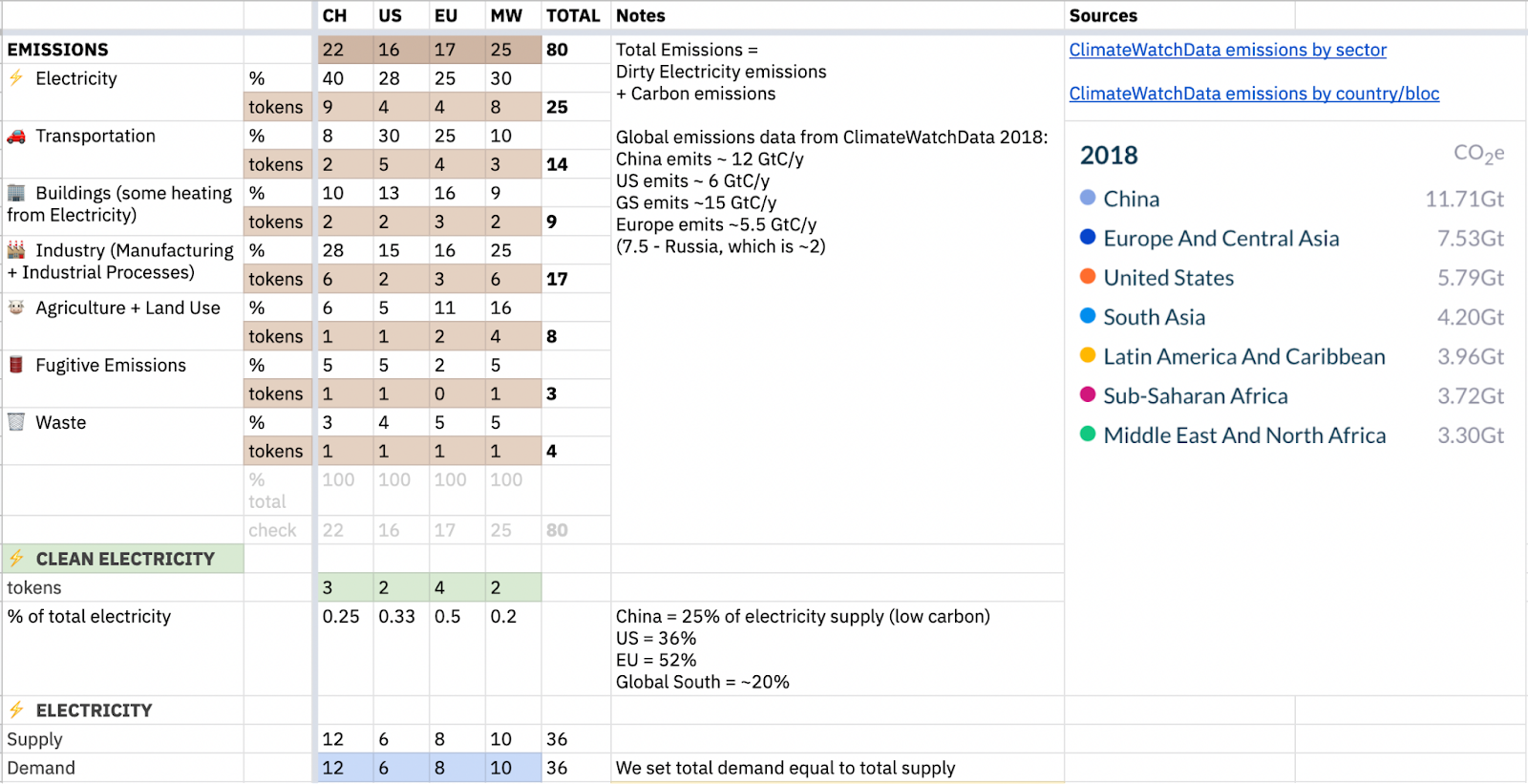

Each player starts with a vast amount of emissions, based on the real-world emissions of the world power they oversee. Round after round, they are challenged to reduce their own emissions, while preserving and boosting collective carbon sinks.

We decided the win condition would trigger the moment emissions stop accumulating in the thermometer, and start to decline instead. In other words, when the planet, through its carbon sinks, can absorb more emissions than human activities generate. That moment is called drawdown.

Drawdown represents a vital milestone. It means we have stopped global warming and reversed the dangerous trend of the last couple of centuries. In the real world, drawdown doesn’t mean the job is done. In order to make our planet habitable for future generations, we must continue to bring down greenhouse gas concentrations to pre-industrial levels. We decided the game won’t model that phase, but instead will focus on the urgent, existential challenge of stopping emissions levels (and therefore temperatures) from rising.

What’s the difference between drawdown and net zero?

Net zero was originally used by climate scientists to describe the moment when globally, the sum of all emissions produced by human activities is equal to the amount of emissions absorbed by carbon sinks. Since then it’s become a rather abused phrase, as many governments and corporations have been dressing up their emission accounting tricks as net zero pledges. Indeed, we found players tend to be more familiar with “net zero” than “drawdown”. That meant our definition of net zero could well be different from what some players might have heard in other contexts. Drawdown allows us to avoid any potential confusion (which is rather important when it comes to evaluating a win condition). It also feels more evocative and ambitious: instead of min-maxing their carbon accounting to reach neutrality, we encourage players to cut emissions as deeply as possible.

And how does it feel to win?

In our early prototypes the game would end immediately after players achieved drawdown. While this made for a clear and explosive moment of joy, it also meant that crises (which come after emissions in the round order) could be ignored by players when they felt they were close to drawdown. This rule was sending the misleading message that once we reach the drawdown milestone, everything will be solved, no more extreme weather events, no more suffering. It also drained a lot of tension from the end game.

We therefore moved the victory check after the resolution of the last round of planetary effects and crisis cards. To recap, when players reach drawdown they know this is going to be the last round. But it’s not over yet, they still need to survive one last crisis step. Will they make it?

If any player’s resilience is low or if they have a dangerous number of communities in crisis (as it often happens in the late game) then the tension is high and you bite your nails until the last crisis card. To use a football analogy, it feels like a 3-2 victory when your team has scored the last goal ten minutes before the end, and relief comes only with the final whistle.

Playful Activism

Designing a game about the climate crisis feels like trying to photograph a rapidly moving subject. Both hopeful and terrifying news keep erupting. So we could tinker on this forever. But we also can’t wait to share this labour of love with the world, and see what you make of it.

As we chased this subject over the last couple of years, we started to filter news articles and net-zero pledges through the lens of Daybreak. We realised what we’ve built is an interactive model that helps us make sense of what is happening (or not happening) on the climate front, and to have deep conversations with our friends about the future of our planet.

We were over the moon to hear from many people that playing Daybreak changed how they understand the problem and its potential solutions.

Playtesters told us that while the game doesn’t shy away from the loss and destabilisation ahead, it’s empowering to play out the

rapid and far-reaching transformations required to stop global warming. To build a sustainable future where everyone can thrive as well as survive.

Daybreak, in its playful blend of climate science, tech, policy and internationalism, reminds us that all this is possible. If we can imagine it, we can make it happen.

Climate change is here, and it won’t go away if we ignore it. But getting involved in climate action doesn't always have to be serious. We can be playful activists. Taking part in social change can be fun!

We hope playing Daybreak helps you zoom out from the chaos, understand the climate crisis, and join the conversation.

That's all for today

We're putting the finishing touches on the

challenge cards, which you'll be able to mix in many different combos to make the game easier or harder, either for individual players or the whole team. Say you survived your first game, but can you do it again while keeping temperatures lower, while avoiding certain technologies, or while creating an even more resilient society?

We can't wait to show you what we've been up to!

M